History of Ayurveda and Thai Yoga

Origins of Indigenous Traditional Thai Medicine and Massage

by

By Anthony B. James D.N.M.(P), N.D. (T), M.D. (AM), D.P.H.C. (h.c.), Ph.D., D.O.M., R.A.A.P., S.M.O.K.H. Academic Dean SomaVeda College of Natural Medicine and Thai Yoga Center (S.C.N.M.).

Indigenous, Traditional Thai Massage (Indigenous Thai Yoga Therapy), also called “Ryksaa Thang Nuad Phaen Boran Thai” or the “ancient Chirothesia (synonymous with Yoga Therapy Thai style/ Thai Yoga Massage) or hands-on healing” of Thailand, is born of a long tradition.[2] This unique system of indigenous, traditional, natural medicine and Yoga therapy finds its ancient roots first in the traditions of classical Ayurveda as far back as the 5th century B.C.E. Subsequently; the Vedic health and medical practices eventually became comice in SE Asia. Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand were heavily influenced by succeeding generations of Buddhist influence, philosophy, training, and procedures. Some form of this traditional medicine has been taught and practiced in various locations for about 2500 years.

When Theravada Buddharrivedives in the region (400-600 C.E.), wast was firmly established as a colloquial and unique variation still founded primarily on its Vedic roots but progressively influenced by the diversity found in early Thailand beginning in the Sukhothai period, followed by the Ayutthaya and Bangkok erStartingning in the Ayutthaya period (1351), we see influences from the Burmese, Japanese, Chinese, Malay, Philipines, and Portugal[3] consistent with the immigration and trade of the Kingdom during that time. This is also when we note the first documented arrival of Western doctors. Traditional Burmese medicine especially came to the forefront before and after the sacking of Ayutthaya between 1765 and 1767 [4]. The classics of Indian literature and Ayurveda were known and being distributed and or used by the Royal Court in Ayutthaya, such as the Ramayana, Rig Veda, Athara Veda, Caraka-Saṃhitā, Pradapika, and Sushruta Samhita. In addition, from its earliest days, the Thai Royal court was likely knowledgeable, by way of local culture and the literature of the Vedas and the Puranas, of the Hindu deities, and in particular, the deity and iconic symbols associated with Dhanvantari (Thai Pra Narai, Narayana, Jagannath). It may be interesting to note that one of the oldest bronze statues in Thailand, now located in the National Museum in the ancient capital of Sukhothai, is that of Vishnu. Dhanvantari is an avatar of Vishnu in Hinduism. He is the physician to the Gods and generally the deity/spiritual icon of Ayurveda.

During the periods of war with neighboring Burma, tens of thousands of Thai people were taken as prisoners and held for over 40 years before establishing their freedom and returning to their homes, including the famous Thai Prince and later King Naresuan [5] [6]. When they returned, they brought knowledge and practices obtained during captivity, including medicine, martial arts, music, food, and more. These were incorporated into the dominant Thai culture and remain influential today in the many generations of Burmese immigrating and living in Thailand.

OM NAMO SHIVAGO

Historically, the initial credit for the origination of what becomes Indigenous, Traditional Thai Medicine and Massage is given to one individual, a famous Indian doctor called Jivaka Komalaboat [12] (Shiv. Otherther spellings include Jivaka Kumar Bhaccha, Jivaka Komarabhacca, and Jivaka Amravana. Jivaka, of Indian origin, is alleged to have been born in what is today the city of Rajgir, the ancient capital of the Magadha Kingdom (Later Majapahit/ Bihar). There are several accounts of his birth, life, education, and teachings.

In looking for more detailed and historically verifiable references to the life of Jivaka. I found several. One specific account crosses references several others; however, without particular concerns, it is hard to verify all details. However, including it under fair use to present facts for further research and or verification: According to one author (Salina- Nalanda University), “According to the Anguttara commentary, he was the son of Salavati, a courtesan of Rajagaha with Abhayarajakumara (Son of Raja Bimbisara) but some accounts maintain Jivaka was Ambapali’s son with Raja Bimbisara. According to Vinaya sources, the child was placed in a basket right after birth and thrown on a dust heap, from which Abhayarajakumara rescued him.

When questioned by Abhaya, people said “he was alive” (jīvati), and therefore the child was called Jivaka; because the prince brought him up, he was called Komārabhacca (child of a Prince). It has been suggested, however, that Komārabhacca meant master of the Kaumarabhrtya science (the treatment of infants); VT.ii.174; in Dvy. (506-18) [12] he is called Kumarabhuta because of his medical profession.

Growing up, he learned of his antecedents, went to Takkasila without Abhaya’s knowledge, and studied medicine for seven years. When he returned to Rajgir, Abhaya established him in his residence. There he cured Bimbisara of a troublesome fistula and received as a reward all the ornaments worn by Bimbisara’s five hundred wives.

PLEASE NOTE Another Jivaka Origin Story from the Pali: Mahavagga 8.1, Chapter 1: Tells of his parentage and how he came to be part of the King Bimbisara’s royal family, his journey to learn medicine, how he was introduced to the sick Buddha and some of his conversation and counseling with the Buddha. Interesting is how he convinced the Buddha to allow the Sangha Monks to wear clean and new robes!

DalhaSa (Dalhaṇa), the 12th-century commentator of the Susruta Samhita, says that Jivaka’s compendium was regarded as one of the authoritative texts. Thus, it spoke Jivaka. Another text that quotes Jivaka’s formulas is the Navantaka (meaning ‘butter’), a part of the Bower Manuscript discovered in 1880 from Kuchar in Chinese Turkistan. Based on earlier standard sources, this medical compilation of the 4th century A.D. attributes two formulas dealing with children’s disease to Jivaka, saying, ‘Iti hovaca Jiv,’ ah,’ i.e…. One formula is: i.e., Bhargi, long pepper, Paha, papaya, together with honey, may be used as linctuses against emeses due to deranged phlegm.” A “Linctus” is a form of cough medicine [13].

In researching Jivaka, Rajgir, and the ancient Nalanda University, there are references to Jivaka and also in connection with the Buddha from the Chinese authors Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang) and Yijing, especially those of Xuanzang (Sixth Century between 630 and 643 CE). In one of his accounts, he writes, “North-east from Srigupta’s Fire-pit, and in a bend of the mountain wall, was a tope (stupa) at the spot where Jivaka, the great physician, had built a hall for the Buddha. Remains of the plants and trees within them still existed. Tathagata often stayed here. Beside the road, the ruins of Jivaka’s private residence still survive.” [14]

Referred to in some ancient references as the Thrice Crowned King of Medicine, he was a classically trained Ayurvedic physician, probably in the tradition of Atreya (Atreya Punarvasu/ Takkasila). Jivaka was known to be influenced by Buddhism and was possibly the personal physician to Raja Bimbisara, the Magadha king of that period, and to the Buddha and local monks community on the appointment of the king.[12]

Today, traveling to see Jivaka’s home and the ancient Nalanda University in Rajgir is possible.

Pali is an anachronistic/ancient Sanskrit language still used today by Theravada Buddhist monks. “Studies in Traditional Indian Medicine in the Pāḷi Canon: Jīvaka and Āyurveda,” (Kenneth G. Zysk, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 5, pp. 309–13) [15]. Jivaka’s name is mentioned in the traditional Pali canon or writings of Theravada (Hinayana) Buddhism (Zysk, Kenneth, G. 1982). There are numerous additional references to him, his life, and his healing practices in the Pali Cannon. There is some support for the idea that the “Giving of Robes” (Vin.i.268-81; AA.i.216) [16], where he made a gift to the Buddha of “a celestial shawl he received from a king named “Chanda Pradyotha” prompting the Buddha to give a famous sermon leading to the practice still followed today.

Another example in the Pali Canon is Jivaka treating the Buddha for specific ailments using Ayurveda. “Once, when the Buddha was ill, Jīvaka found it necessary to administer a purge, and he had fat rubbed into the Buddha’s body and gave him a handful of lotuses to smell. Jīvaka was away when the purgative acted and suddenly remembered that he had omitted to ask the Buddha to bathe in warm water to complete the cure. The Buddha read his thoughts and bathed as required. (Vin.i.279f; DhA. (ii.164f)” [17]

The above is an example of the therapeutic adjuncts used in I.T.T.M. today: Chirothesia, Anointing, Oliation, Herbology, Aromatherapy, Pancha Karma, Marma Cichitsa, etc.

He became a Buddhist monk (Sotāpanna) while with the Buddha. He continued to practice medicine and develop the strategies that would be the foundation for medical and healing practice in Buddhist temples until today.

Jīvaka was eventually declared by the Buddha chief among his lay followers and loved by the people (“aggam puggalappasannānam“) (A.i.26)[18]. He is included in a list of good men who have been assured of realizing deathlessness (A.iii.451; DhA.i.244, 247; J.i.116f) [19].

He seemed to follow, teach and or exemplify the doctor’s moral obligations (Doctor’s Code of Conduct) as found in the Pali scripture, the Vejjavatapada. It is attributed to actual practices and teaching directly from the Buddha. In the seven articles, excerpts from four passages in the Pali canon, the Buddha lays down the attitudes and skills which would make “one who would wait on the sick qualified to nurse the sick.” (Anguttara Nikaya III, p.144) [20]. The Vejjavatapada likely predates the Greek Hippocratic Oath. It does not just encourage doctors to practice ethically; it specifies a truly holistic practice of medicine addressing the spirit, mind, and body in an integrated fashion.

“The Lord said: “Health is the greatest gain.” He also said: “He who would minister to me should minister to the sick.”

I, too, think that health is the most significant gain, and I would minister to the Buddha.

Therefore:

(A) I will use my skill to restore the health of all beings with sympathy, compassion, and heedfulness.

(B) I will be able to prepare medicines well.

(C) I know what medicine is suitable and what is not. I will not give the unsuitable, only the suitable.

(D) I minister to the sick with a mind of love, not out of a desire for gain.

(E) I remain unmoved when I have to deal with stool, urine, vomit, or saliva.

(F) Occasionally, I can instruct, inspire, enthuse, and cheer the sick with Teaching.

(G) Even if I cannot heal a patient with the proper diet, medicine, and nursing, I will still minister to him out of compassion.

Translated from Pali into English by Bhante Shravasti Dhammika”

The Brahmajala Sūtra says: “If a disciple of the Buddha sees anyone sick, he should provide for that person’s needs as if he were making an offering to the Buddha.” [12] Brahma Net Sutra, S.T.C.U.S.C., New York, 1998, VI,9[21]’

Jivaka is revered to this day. Many modern practitioners and schools begin every healing session by reciting a Pali Mantra called OM NAMO SHIVAGO. Royal practitioners generally do this quietly, while in the North of Thailand, the Mantra may be recited out loud, sometimes with the receiver participating as well.

The Wai Khruu, or paying of respect to Jivaka (Shivago), is still partly to remember his contribution to present-day art. To what extent other styles of medicine and massage have contributed to Indigenous, Traditional Thai Medicine (T.T.M./ I.T.T.M.) development is impossible.

The current capital of Thailand, Bangkok, was established in 1782 with the coronation of Chakri King Rama I 1782. According to Thai historians, the first meaningful building erected in the new capital was rebuilding the new Wat Pho (1789-1801). The original in the former capital (Ayutthaya) has been burned by invading Burmese armies.

Primarily I.T.T.M. has been passed from generation to generation as an oral tradition. One would serve an apprenticeship under a teacher, often for several years, before practicing as a practitioner. In general, the monks and nuns of the Buddhist Temples preserved and cherished the teachings. In addition to the oral tradition, there have been several treatises, handwritten papers, Codices, and books written chiefly for or by the Royal Court and not easily obtained by the general public. The most accessible documents detailing the Royal Court Traditional Medicine practices were the stone carvings built into the walls and pavilions of Wat Po in Bangkok. More on these later.

Important to note also is that there have always been, from the earliest days to the present, two different corollary systems of practice: Two types of traditional curing methodologies and points of view in the way healing and conventional medicine were practiced in Thailand. The urban or variant descendant practice from the Royal Schools of traditional medicine and the country/ rural and standard practices found in the village, jungle, and countryside.[22] The urban represents efforts at standardization and training, and the rustic or country incorporates the more indigenous ideas and practices restricted by tribe or geographic location. Most researchers agree that there has always been and still is cross-sharing of both systems’ ideas, influences, and procedures.

Similar variations of this indigenous traditional medicine are practiced in Sri Lanka, Burma, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand. There is also a dramatic similarity to Traditional Tibetan Medicine, Amma/Tui Na of China, the Anma/Shiatsu of Japan, and Filipino Hilot.

History is unclear when specific developments were incorporated into the standard medicine catalog of practices. Additionally, there is a lack of documentation of the family, tribal, and village-specific practices passed on through oral tradition and not documented in the “official” and sanctioned records and historical text. A further example is the historical and contemporary significant differences between “Official” Traditional Medicine practices and the “Rural” traditional medicine practices found in remote villages and among tribal communities.

We don’t see the first official documentation until King Rama commissions the medical tablets (epigraphies) made and enshrined at the new Wat Pho in the 1830s. According to the custodians of Wat Pho, after the capital (Ayutthaya) was destroyed in 1767 by Burmese invaders, King Rama used rescued fragments of the original documents to make the new ones.[2]

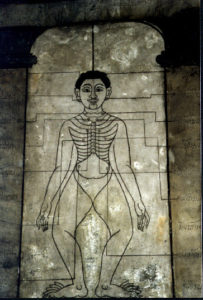

These tablets are a text of the theory behind I.T.T.M. and show the Sen or lines of energy running throughout the body.

These charts of stone depict sixty figures, thirty of the front and thirty of the back. There are channels and points displayed. One interesting observation is apparent: many channels directly correspond to Chinese meridians and unique or Extraordinary vessels. Others reach to the concepts of Prana Nadis from classic Indian Ayurvedic medical science. The charts detail major and minor Marma/ Chakras or energy centers. In Traditional Thai Medicine, these centralized energy/wind/breath/air point locations are called “Lom” or Wind Gates.

“Chart depicting female balancing points: Wat Po Massage Pavilion”

The depiction of the knowledge of traditional medicine at Wat Po (Bangkok) and Wat Raja Orasaram Ratchaworawiharn (Thonburi) was considered incomplete. This was perhaps intentional as the “Secrets” of healing practiced by the Royal Court Doctors (Maw Nuad) at that time were closely guarded. The Royal practice of medicine was more likely passed on from one generation to the next within the family… father to son or nephew in a formal apprenticeship.

In addition to the famous “Epigraphies of King Rama” ( Carved stone medical text) located at Wat Po and Wat Raja-Orasarem (King Rama III: in the Thai/ Chinese style called “The Royal Favorable Art” style), there are also gunite statues of Thai Reishi Yogis practicing the various Asana or traditional Yoga postures – The Thai variation of Hatha Yoga or self-treatment. In the past, more than 100 exciting figures were scattered about Wat Po’s courtyards. However, many were damaged or deteriorated due to weathering and have been retired for preservation. The Yoga of the Thai Reishi is referred to as Reusi Dottan.

In Thailand’s past, the people came to the temples for just about everything from medical help to education. Anyone could come to the temple for food, shelter, medical or spiritual healing. I.T.T.M. (Traditional Thai Medicine/Traditional Thai Massage) contributed to the ancient Thais’ emotional, physical, and spiritual well-being, which continues to do so today.

Thai culture blends many cultures from east to west (India to China and Tibet to Indonesia), and I.T.T.M. reflects this. Presently, there are two primary schools of indigenous traditional Thai medicine (Thai Ayurveda), indigenous traditional Thai massage (Thai Yoga- Marmachikitsa), and several minor ones. Many private teachers, monks, and nuns also pass on multi-generational teachings in the oral tradition. Many of these are very knowledgeable, having grown up in families practicing for several generations.

It is relatively recent in Thailand’s history (the 1990s) that the Royal Thai Government, under various ministries, has shown interest and dedicated efforts to catalog the different traditional schools and teachers from the entire country. Initially, the emphasis was on the “official” or Bangkok styles and schools, and over the years, broader research has involved many more variations. There is now standardized practice and curriculum for the traditional techniques under the Union of Thai Traditional Medicine Society (U.T.T.S.), which has been recognized by the United Nations[22] formally as the Indigenous Traditional Medicine of Thailand (1978: WHO UN DESA, recognition Indigenous and Traditional Medicine).

There are famous and well-known traditional schools such as the Traditional College of Medicine, Wat Pho, Bangkok; Wat Raja Orasanam, Thonburi; Anantasuk School of Thai Traditional Medicine: Wiangklaikangwan Industrial College: Hua Hin and Lak Sii (Aachan, Phaa Khruu Anantasuk); Ayurved Vidyalay: Bangkok and the Foundation of Shivago Komarpaj, Buntautuk Old Medical Hospital in Chiang Mai (Founded by Ajahn, Phaa Khru Sintorn Chaichagun in 1973). There are also satellite or derivative medical schools in the Wat Po tradition in various areas outside Bangkok in Lamphun and Chiang Mai.

Indigenous, Traditional Thai Medicine and Massage are also taught in other local temples, temple auxiliaries, and by various competent individuals from Chiang Mai to Sri Lanka. I refer to the Wat Sawankhalok Medicine School for the Blind (Aachan Moh Tawee), The School of Traditional Medicine at Wat Suan Dok in Chiang Mai, and Wat Amperwa, as well as traditional sword fighting schools such as the Buddhai Swan Institute, formerly located in Nongkham and now in Ayutthaya. The practices of I.T.T.M. are found in the Muay Boran and Muay Thai Boxing Traditions. Lastly, you see the techniques and Ayurvedic influences in the Reusi Dottan or “Reishi/Yogi” still practiced and experiencing a renewed interest.

Formal education for Thai Traditional Doctors is now carried out at the University level: (This list is not comprehensive)

1) Wiangklaikangwan Industrial College, Hua Hin

2) Rajamangala Institute of Technology: Thai Traditional Medicine College, Songkla

3) Burapha University: The College of Abhaibhubejhr Thai Traditional Medicine, Chon Buri

4) Muban Chombueng Rajbhat University

5) Prince of Songkla University

6) Mahidol University: Siriraj Medical School

Bibliography

[2] Brun and Schumacher: “Traditional Herbal Medicine in Northern Thailand”: 1994 edition, White Lotus, Bangkok, Thailand.

[3] Barbara Andaya, “Political Development between the Sixteenth and Eighteenth Centuries” in The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Volume One, Part Two, from c.1500 to c.1800 (Singapore: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 66-67.

[4] Anthony Reid, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce 1450-1680—Volume Two, Expansion and Crisis (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993), 69.

[5] David Wyatt, Thailand: A Short History (New haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982), 104.

[6] William A. R. Wood, A History of Siam (Bangkok: Chalermnit Bookshop, 1959), 146.

[12] Jivaka-Komarabhacca in Pali Cannon: http://www.palikanon.com/english/pali_names/j/jiivaka.htm

[13] Jivaka called” Komarabhaca: “The treatment of infants,” VT.ii.174; in Dvy. (506-18)

[14} Jivaka: http://nalanda-insatiableinoffering.blogspot.com/2010/06/jivaka-amravana.html

[15] Jivaka name documented in Pali Cannon: Studies in Traditional Indian Medicine in the Pāḷi Canon: Jīvaka and Āyurveda”, (Kenneth G. Zysk, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 5, pp. 309–13, 1982)

[16] Jivaka: “Giving of Robes” (Vin.i.268-81; AA.i.216)

[17] Jivaka treats Buddha’s ailments: Buddha reads Jivaka’s thoughts and bathes as required: Vin.i.279f; DhA. (ii.164f)

[18] Jivaka declared by the Buddha chief among his lay followers loved by the people (aggam puggalappasannānam) (A.i.26)

[19] Jivaka is included in a list of good men who have been assured of the realization of deathlessness (A.iii.451; DhA.i.244, 247; J.i.116f)

[20] Jivaka and Vejjavatapada: In the seven articles, excerpts from four passages in the Pali canon, the Buddha lays down the attitudes and skills which would make “one who would wait on the sick qualified to nurse the sick.” “Doctors Code of Conduct”: Anguttara Nikaya III, p.144 (The Vejjavatapada likely predates the Greek Hippocratic Oath.)

[21] Provide for the sick: Brahma Net Sutra, S.T.C.U.S.C., New York, 1998, VI,9.

[22] Traditional Medicine in the Kingdom of Thailand: http://www.searo.who.int/entity/medicines/topics/traditional_medicines_in_the_kingdom_of_thailand.pdf?ua=1

All Information about Thai Traditional Medicine, SomaVeda® Thai Yoga/”Thai Yoga Reduces Psychological Stress,” is presented solely as an opinion for educational purposes and is provided as an opinion for educational purposes only and is not intended to be used for any therapeutic purpose, neither is it intended to diagnose, prevent, treat or cure any disease. It is not a substitute for competent medical advice regarding any medical condition. Please consult a health care professional for diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions. At the same time, all attempts have been made to ensure the accuracy of this information. The author and ThaiMassage.Com do not accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions.

Copyright© 2016, Anthony B. James, All rights reserved under International and Pan-American copyright conventions. World rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries should be addressed to Anthony B. James, 5401 Saving Grace Ln. Brooksville, FL 34602 · https://thaiyogacenter.com

Comments are closed.